Code

# load packages

library(ggplot2)

library(tibble)

library(dplyr)

library(kableExtra)December 9, 2024

When I started my PhD in pharmacometrics, I wanted to try something fancy1: specifying a combined proportional and additive error model in NONMEM for one of my projects. A colleague kindly sent me a reference model, and to my confusion, the code included a novel way (at least to me) of defining residual unexplained variability (RUV):

It wasn’t immediately clear why it was set up this way, and I was left with some questions:

$SIGMA block fixed to 1? And why only one entry, given we have both proportional and additive components?SD?THETA(1) and THETA(2)?It seemed a bit odd to me. I was more familiar with defining RUV directly in the $SIGMA block, something like:

or maybe in a slightly more elegant form:

So, why use this “alternative”2 way of defining the error? Before we try to explain this way of writing a combined error model to ourselves, let’s break down the additive and proportional error model separately to understand what’s going on. Please note: most of this content can also be found elsewhere (Proost 2017).

The “classical” way (if I can call it that) of specifying an additive error model in NONMEM is as follows:

In this approach, RUV is defined directly in the $SIGMA block, where EPS(1) is assumed to be normally distributed with a mean of 0 and variance of 0.0529:

\[EPS(1) \sim \mathcal{N}(0,0.0529)\]

It is quite important to note that we are specifying variances in $SIGMA. Now the alternative way (my colleague called it the Uppsala way3) of coding the additive error model looks like this:

Here, $SIGMA is fixed so EPS(1) has a variance of 1, effectively making it a standard normal distribution:

\[EPS(1) \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)\]

But we then multiply this random variable EPS(1) by a scaling factor SD_ADD (which is being estimated as a THETA parameter) before the product is being added to the individual predicted IPRED value:

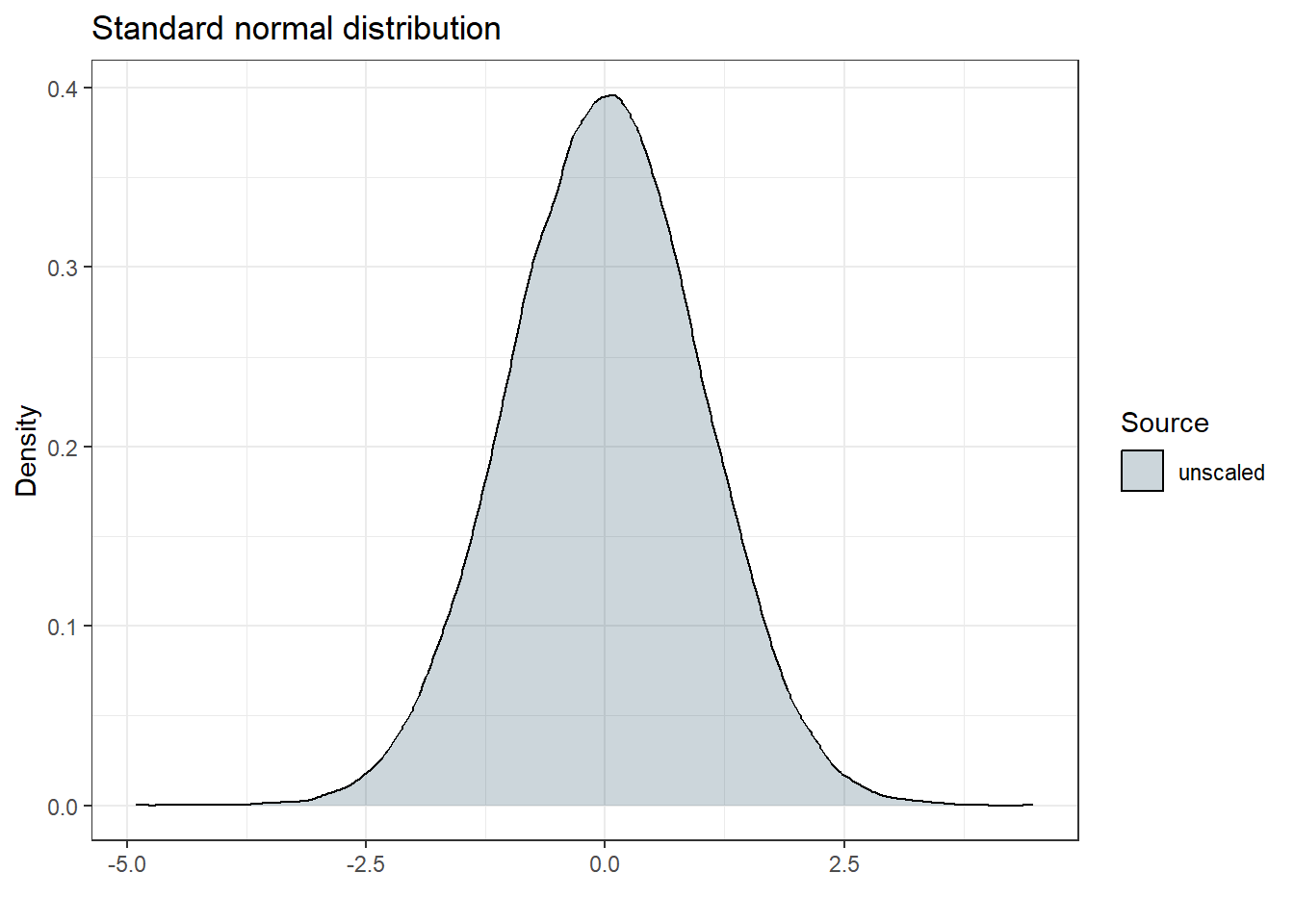

I am not super familiar what happens if we multiply a random variable with a scaling factor. So maybe it is a good idea to visualize what happens when we fix $SIGMA to 1 and multiply it by SD = 0.23. Let’s start with plotting a standard normal distribution ($SIGMA 1 FIX):

# sample from standard normal distribution

x <- rnorm(100000, mean = 0, sd = 1)

std_norm <- tibble(x = x, source = "unscaled")

# plot

std_norm |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, fill = source)) +

geom_density(alpha=0.2)+

labs(title = "Standard normal distribution", x = "", y = "Density")+

scale_fill_manual(

"Source",

values = c(

"unscaled" = "#003049"

)

) +

theme_bw()

The resulting standard deviation should be 1, and since \(1^2 = 1\), the resulting variance should also be 1. Let’s be sure and check our empirical estimates (it is a simulation, after all) to confirm this:

| Source | Standard Deviation | Variance |

|---|---|---|

| unscaled | 1 | 1 |

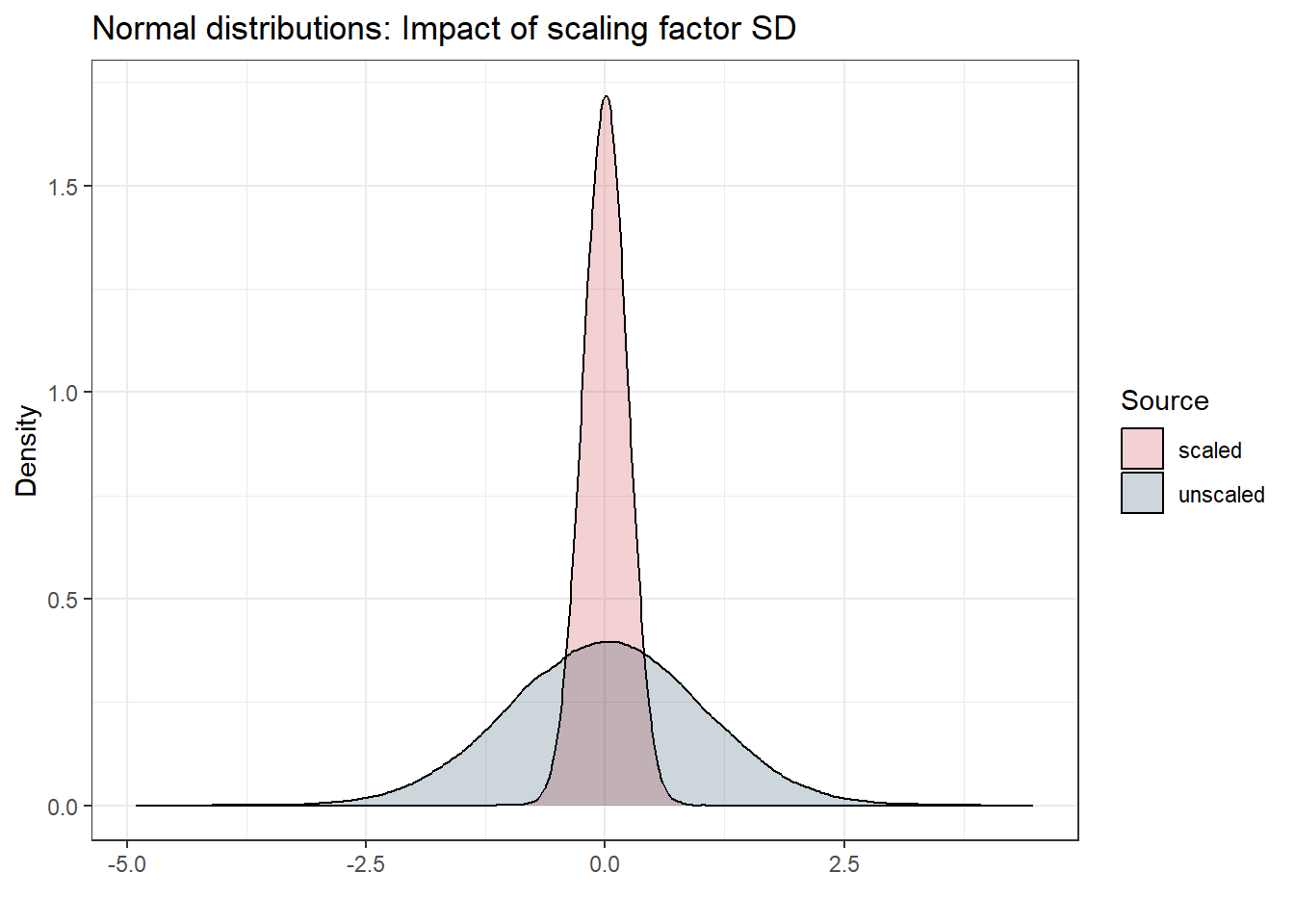

Good. But what happens now to this standard normal distribution if we multiply the random variable with some scaling parameter \(SD = 0.23\)? Let’s find out:

# set a seed

set.seed(123)

# multiply with W

SD <- 0.23

x_scaled <- x * SD

std_norm_scaled <- tibble(x = x_scaled, source = "scaled")

# combine both

std_norm_combined <- bind_rows(std_norm, std_norm_scaled)

# plot

std_norm_combined |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, fill = source)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.2)+

labs(title = "Normal distributions: Impact of scaling factor SD", x = "", y = "Density")+

scale_fill_manual(

"Source",

values = c(

"unscaled" = "#003049", # Blue color for original

"scaled" = "#c1121f" # Orange color for scaled

)

) +

theme_bw()

Let’s compare the standard deviation and variance of both distributions:

| Source | Standard Deviation | Variance |

|---|---|---|

| scaled | 0.23 | 0.053 |

| unscaled | 1.00 | 1.000 |

For the scaled distribution, we can see that the resulting standard deviation \(\sigma\) is approximately equal to our scaling factor SD_ADD (which is 0.23) and the variance is \(0.23^2 \approx 0.053\). This means that in our model code

the SD_ADD parameter (specified via $THETA) is representing a standard deviation. Cool thing! Probably it’s not too surprising given my naming scheme, but anyways.4 Overall, both of these models should be equivalent:

and

To sum it up: We need to be careful with the units. If we use the classical way, we are estimating a variance via $SIGMA, but if we use the alternative way, we are estimating a standard deviation via $THETA and fix the $SIGMA to a standard normal. Typically, we would report the standard deviation (rather than the variance) if we use an additive model, and I think one of the advantages of the alternative way is that we directly read out the standard deviation from the parameter estimates (without the need to transform anything). Some also say that the estimation becomes more stable if we model the stochastic parts via $THETA, but I cannot judge if this is true or not.

Whenever we have an additive error model and we specify the RUV in the $THETA block (the alternative way), the resulting estimate is a standard deviation.

Now, let’s look at proportional error models. The classical way of specifying the proportional error model looks like this:

And the alternative way is:

The structure is similar to the additive model we discussed earlier, except that the standard deviation of the random noise around our prediction depends on the prediction itself. This is why we first calculate the standard deviation SD_PROP at the given prediction as:

This already gives us an understanding of the units of THETA(1): it represents the coefficient of variation (CV) of the prediction IPRED. Why? A coefficient of variation represents the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean. This is why we end up with a standard deviation (SD_PROP) if we multiply the prediction (IPRED) with the CV (THETA(1)). So we always have a fraction of the prediction representing our standard deviation at that point.

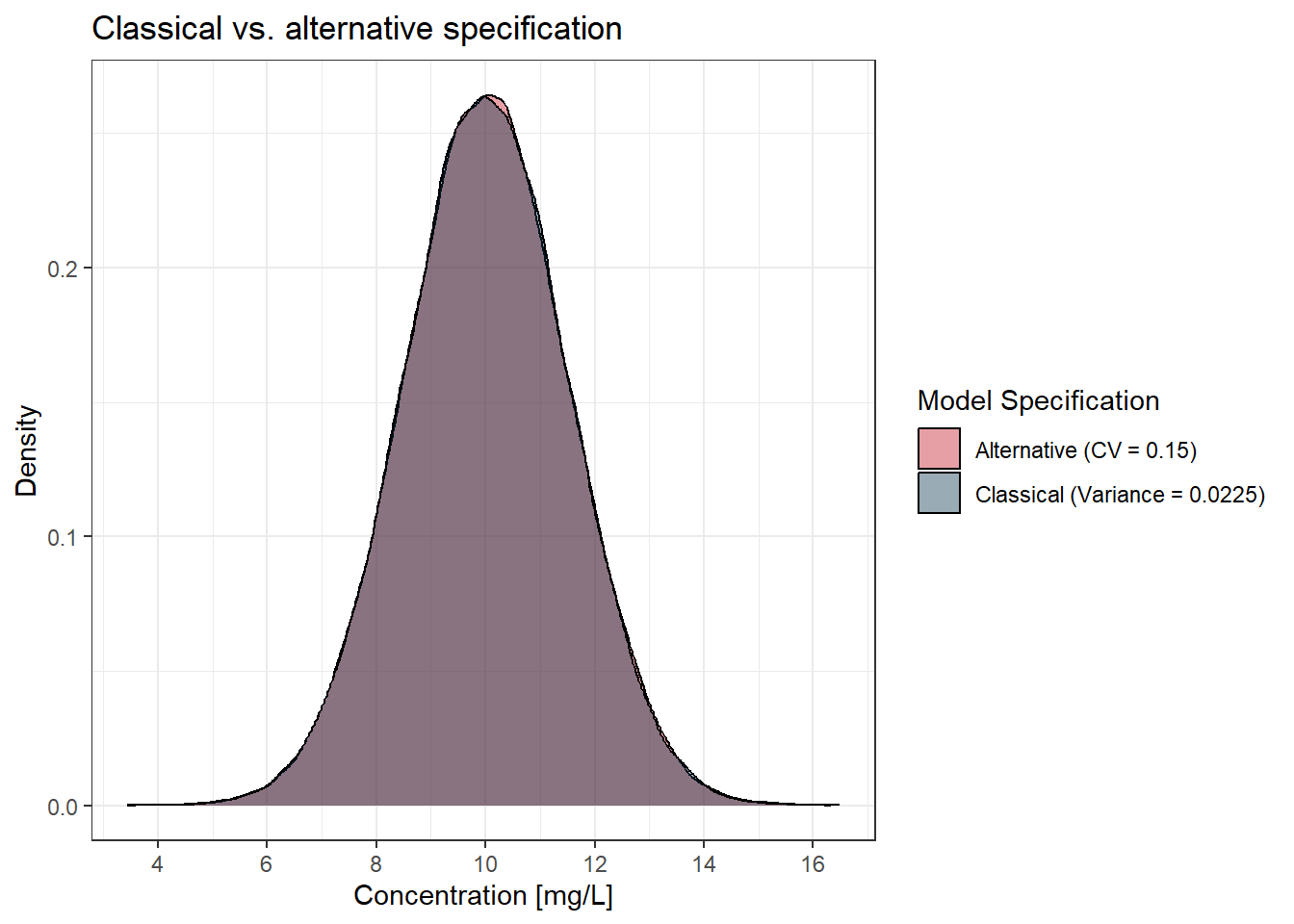

Suppose we have a prediction (IPRED) of 10 mg/L and we want to show the resulting distribution. For the classical approach, we would specify a variance (EPS(1)) of 0.0225, and for the alternative way, we would specify a CV (THETA(1)) of 0.15. What do you think? Will this be equivalent or not? Let’s find out!

# Set seed for reproducibility

set.seed(123)

# Parameters

IPRED <- 10

CV_percent <- 0.15

SD_prop <- CV_percent * IPRED

sd_classical <- IPRED * sqrt(0.0225)

# Number of samples

n <- 100000

# Classical way: Specify variance directly

eps_classical <- rnorm(n, mean = 10, sd = sd_classical)

# Alternative way: Specify CV%

eps_alternative <- rnorm(n, mean = 10, sd = 1 * SD_prop)

# Create a tibble combining both distributions

prop_models <- tibble(

value = c(eps_classical, eps_alternative),

source = rep(c("Classical (Variance = 0.0225)", "Alternative (CV = 0.15)"), each = n)

)

# Plot the density of both distributions

prop_models |>

ggplot(aes(x = value, fill = source)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.4) +

labs(

title = "Classical vs. alternative specification",

x = "Concentration [mg/L]",

y = "Density"

) +

scale_fill_manual(

"Model Specification",

values = c(

"Classical (Variance = 0.0225)" = "#003049", # Blue

"Alternative (CV = 0.15)" = "#c1121f" # Red

)

) +

scale_x_continuous(breaks=c(4,6,8,10,12,14,16))+

theme_bw()

Both models end up with the same distribution. In the classical way, we are given a variance of 0.0225. To get the standard deviation, we take the square root of the variance:

\[

\sigma_{EPS} = \sqrt{0.0225} = 0.15

\] This means, that our random variable EPS(1) has a standard deviation of 0.15 mg/L in our classical model:

By multiplying this EPS(1) by the prediction (IPRED) of 10 mg/L, we are scaling this random variable to have the (desired) standard deviation of the prediction distribution (PRED):

\[ \sigma_{Y} = 0.15 \times 10 = 1.5 \, \text{mg/L} \]

In the alternative way, we are directly estimating the coefficient of variation (CV) as 0.15.

We are first calculating the respective standard deviation (SD_PROP) by multiplying CV with IPRED. We then turn this standard deviation into a random variable with this standard deviation by multiplying it with a random variable from a standard normal (EPS(1)). Also here, the respective standard deviation of the prediction distribution (PRED) is 1.5 mg/L:

\[ \sigma_{Y} = 0.15 \times 10 = 1.5 \, \text{mg/L} \]

In both cases, the resulting variability is the same, meaning both approaches lead to the same standard deviation of 1.5 mg/L. Again, it is a bit more convenient to specify the CV directly, as it is more intuitive and easier to interpret. And if the stability argument is true (see above), we would also make our estimation more robust this way.

Whenever we have a proportional error model and we specify the RUV in the $THETA block, the resulting estimate is a coefficient of variation.

Finally, let’s combine our knowledge to understand the alternative way of specifying a combined proportional and additive error model:

Two parts should already be familiar:

In the first part, we calculate SD_PROP, representing the resulting standard deviation of the proportional part (as THETA(1) is a CV). The second part, SD_ADD, gives us the standard deviation of the additive part. Now we want to find the joint standard deviation SD at the given concentration. But how do we combine these components?

We can see that we first square both terms, then add them together, then take the square root. Sounds complicated - why not just add them directly together? This is because variances are additive when combining independent random variables, while standard deviations are not (Soch 2020). Written a bit more formally for two independent random variables (we typically assume the covariance to be 0 when modelling RUV):

\[\mathrm{Var}(X + Y) = \mathrm{Var}(X) + \mathrm{Var}(Y)\] In our case, SD_PROP and SD_ADD are standard deviations, so we must first square them to get the variances and then add them. However, we want to go back to a standard deviation before we multiply SD with EPS(1) (being fixed to 1). Therefore, we take the square root in the end.

This operation has always confused me a bit, but once I understood that I can sum up variances, but not standard deviations 5 it made more sense to me.

When specifying a combined error model, the estimates in the $THETA block represent a standard deviation for the additive part and a coefficient of variation for the proportional part.

This is a somewhat lengthy explanation of why and how we code the alternative approach in NONMEM. Personally, I wasn’t very familiar with how distributions behave when its random variable is being multiplying by a factor, and I didn’t realize that while variances are additive when combining two random processes, standard deviations are not. If you have a stronger background in statistics, this might have been obvious, but I hope this explanation was still helpful for some others.

Yeah, I know, not really fancy. But that’s how it feels when you touch a combined error model for the first time.↩︎

For many of you, this is likely quite standard. The naming reflects my perspective.↩︎

I’m not sure if this was initially introduced by one of the Uppsala groups or if this is just some hearsay.↩︎

Some people also code it with W instead of SD but it’s always a good idea to find descriptive variable names.↩︎

Probably something you would tackle in the first semester of your statistics studies. But not if you study pharmacy ;)↩︎

@online{klose2024,

author = {Klose, Marian},

title = {Expressing {RUV} as {\$THETA} in {NONMEM}},

date = {2024-12-09},

url = {https://marian-klose.com/posts/expressing_ruv_as_theta/index.html},

langid = {en}

}

---

title: "Expressing RUV as $THETA in NONMEM"

description: "Have you ever been confused why some people use the $THETA block to code their RUV in NONMEM? You are not alone!"

author:

- name: Marian Klose

url: https://github.com/marianklose

orcid: 0009-0005-1706-6289

date: 12-09-2024

categories: [RUV, Error, NONMEM]

image: preview.jpg

draft: false

echo: true

execute:

freeze: true # never re-render during project render (dependencies might change over time)

echo: true

message: false

warning: false

citation:

url: https://marian-klose.com/posts/expressing_ruv_as_theta/index.html

format:

html:

number-sections: true

toc: true

code-fold: true

code-tools: true

---

```{r}

# load packages

library(ggplot2)

library(tibble)

library(dplyr)

library(kableExtra)

```

When I started my PhD in pharmacometrics, I wanted to try something fancy[^1]: specifying a combined proportional and additive error model in NONMEM for one of my projects. A colleague kindly sent me a reference model, and to my confusion, the code included a novel way (at least to me) of defining residual unexplained variability (RUV):

```{r filename="alternative way (combined)"}

#| eval: false

#| collapse: false

#| code-fold: false

$THETA

0.15 ; RUV_PROP

0.23 ; RUV_ADD

$ERROR

IPRED = F

SD_PROP = THETA(1)*IPRED

SD_ADD = THETA(2)

SD = SQRT(SD_PROP**2 + SD_ADD**2)

Y = IPRED + SD * EPS(1)

$SIGMA

1 FIX

```

It wasn’t immediately clear why it was set up this way, and I was left with some questions:

- Why is the RUV in the `$SIGMA` block fixed to 1? And why only one entry, given we have both proportional and additive components?

- What's with the scaling parameter `SD`?

- Why are we squaring the proportional and additive error components and then taking the square root?

- How do we interpret the units for `THETA(1)` and `THETA(2)`?

It seemed a bit odd to me. I was more familiar with defining RUV directly in the `$SIGMA` block, something like:

```{r filename="classical way v1"}

#| eval: false

#| collapse: false

#| code-fold: false

$ERROR

IPRED = F

Y = IPRED + IPRED * EPS(1) + EPS(2)

$SIGMA

0.0225

0.0529

```

or maybe in a slightly more elegant form:

```{r filename="classical way v2"}

#| eval: false

#| collapse: false

#| code-fold: false

Y = IPRED * (1 + EPS(1)) + EPS(2)

```

So, why use this “alternative”[^2] way of defining the error? Before we try to explain this way of writing a combined error model to ourselves, let's break down the additive and proportional error model separately to understand what's going on. Please note: most of this content can also be found elsewhere [@proostCombinedProportionalAdditive2017].

## Additive error models

The "classical" way (if I can call it that) of specifying an additive error model in NONMEM is as follows:

```{r filename="classical way (additive)"}

#| eval: false

#| collapse: false

#| code-fold: false

$ERROR

IPRED = F

Y = IPRED + EPS(1)

$SIGMA

0.0529

```

In this approach, RUV is defined directly in the `$SIGMA` block, where `EPS(1)` is assumed to be normally distributed with a mean of 0 and variance of 0.0529:

$$EPS(1) \sim \mathcal{N}(0,0.0529)$$

It is quite important to note that we are specifying variances in `$SIGMA`. Now the *alternative* way (my colleague called it the *Uppsala way*[^3]) of coding the additive error model looks like this:

```{r filename="alternative way (additive)"}

#| eval: false

#| collapse: false

#| code-fold: false

$THETA

0.23 ; RUV_ADD

$ERROR

IPRED = F

SD_ADD = THETA(1)

Y = IPRED + SD_ADD * EPS(1)

$SIGMA

1 FIX

```

Here, `$SIGMA` is fixed so `EPS(1)` has a variance of 1, effectively making it a standard normal distribution:

$$EPS(1) \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)$$

But we then multiply this random variable `EPS(1)` by a scaling factor `SD_ADD` (which is being estimated as a `THETA` parameter) before the product is being added to the individual predicted `IPRED` value:

```{r filename="alternative way (additive)"}

#| eval: false

#| collapse: false

#| code-fold: false

Y = IPRED + SD_ADD * EPS(1)

```

I am not super familiar what happens if we multiply a random variable with a scaling factor. So maybe it is a good idea to visualize what happens when we fix `$SIGMA` to 1 and multiply it by `SD = 0.23`. Let's start with plotting a standard normal distribution (`$SIGMA 1 FIX`):

```{r}

# sample from standard normal distribution

x <- rnorm(100000, mean = 0, sd = 1)

std_norm <- tibble(x = x, source = "unscaled")

# plot

std_norm |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, fill = source)) +

geom_density(alpha=0.2)+

labs(title = "Standard normal distribution", x = "", y = "Density")+

scale_fill_manual(

"Source",

values = c(

"unscaled" = "#003049"

)

) +

theme_bw()

```

The resulting standard deviation should be 1, and since $1^2 = 1$, the resulting variance should also be 1. Let's be sure and check our empirical estimates (it is a simulation, after all) to confirm this:

```{r}

# summarize data and calculate sd and variance

std_norm |>

group_by(source) |>

summarize(

sd = sd(x) |> signif(digits = 3),

var = var(x) |> signif(digits = 3)

) |>

rename(

"Source" = source,

"Standard Deviation" = sd,

"Variance" = var

) |>

kbl() |> kable_styling()

```

Good. But what happens now to this standard normal distribution if we multiply the random variable with some scaling parameter $SD = 0.23$? Let's find out:

```{r}

# set a seed

set.seed(123)

# multiply with W

SD <- 0.23

x_scaled <- x * SD

std_norm_scaled <- tibble(x = x_scaled, source = "scaled")

# combine both

std_norm_combined <- bind_rows(std_norm, std_norm_scaled)

# plot

std_norm_combined |>

ggplot(aes(x = x, fill = source)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.2)+

labs(title = "Normal distributions: Impact of scaling factor SD", x = "", y = "Density")+

scale_fill_manual(

"Source",

values = c(

"unscaled" = "#003049", # Blue color for original

"scaled" = "#c1121f" # Orange color for scaled

)

) +

theme_bw()

```

Let's compare the standard deviation and variance of both distributions:

```{r}

# summarize data and calculate sd and variance

std_norm_combined |>

group_by(source) |>

summarize(

sd = sd(x) |> signif(digits = 2),

var = var(x) |> signif(digits = 2)

) |>

rename(

"Source" = source,

"Standard Deviation" = sd,

"Variance" = var

) |>

kbl() |>

kable_styling()

```

For the scaled distribution, we can see that the resulting standard deviation $\sigma$ is approximately equal to our scaling factor `SD_ADD` (which is 0.23) and the variance is $0.23^2 \approx 0.053$. This means that in our model code

```{r filename="alternative way (additive)"}

#| eval: false

#| collapse: false

#| code-fold: false

SD_ADD * EPS(1)

```

the `SD_ADD` parameter (specified via `$THETA`) is representing a standard deviation. Cool thing! Probably it's not too surprising given my naming scheme, but anyways.[^4] Overall, both of these models should be equivalent:

```{r filename="classical way (additive)"}

#| eval: false

#| collapse: false

#| code-fold: false

$SIGMA

0.0529 ; variance

```

and

```{r filename="alternative way (additive)"}

#| eval: false

#| collapse: false

#| code-fold: false

$THETA

0.23 ; standard deviation

$SIGMA

1 FIX

```

To sum it up: We need to be careful with the units. If we use the *classical* way, we are estimating a variance via `$SIGMA`, but if we use the *alternative* way, we are estimating a standard deviation via `$THETA` and fix the `$SIGMA` to a standard normal. Typically, we would report the standard deviation (rather than the variance) if we use an additive model, and I think one of the advantages of the *alternative* way is that we directly read out the standard deviation from the parameter estimates (without the need to transform anything). Some also say that the estimation becomes more stable if we model the stochastic parts via `$THETA`, but I cannot judge if this is true or not.

::: callout-tip

## Specifying additive RUV via \$THETA gives us a standard deviation

Whenever we have an additive error model and we specify the RUV in the `$THETA` block (the *alternative* way), the resulting estimate is a standard deviation.

:::

## Proportional error models

Now, let’s look at proportional error models. The *classical* way of specifying the proportional error model looks like this:

```{r filename="classical way (proportional)"}

#| eval: false

#| collapse: false

#| code-fold: false

$ERROR

IPRED = F

Y = IPRED + IPRED * EPS(1)

$SIGMA

0.0225

```

And the *alternative* way is:

```{r filename="alternative way (proportional)"}

#| eval: false

#| collapse: false

#| code-fold: false

$THETA

0.15 ; RUV_PROP

$ERROR

IPRED = F

SD_PROP = IPRED * THETA(1)

Y = IPRED + SD_PROP * EPS(1)

$SIGMA

1 FIX

```

The structure is similar to the additive model we discussed earlier, except that the standard deviation of the random noise around our prediction depends on the prediction itself. This is why we first calculate the standard deviation `SD_PROP` at the given prediction as:

```{r filename="alternative way (proportional)"}

#| eval: false

#| collapse: false

#| code-fold: false

SD_PROP = IPRED * THETA(1)

```

This already gives us an understanding of the units of `THETA(1)`: it represents the coefficient of variation (CV) of the prediction `IPRED`. Why? A coefficient of variation represents the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean. This is why we end up with a standard deviation (`SD_PROP`) if we multiply the prediction (`IPRED`) with the CV (`THETA(1)`). So we always have a fraction of the prediction representing our standard deviation at that point.

### An example

Suppose we have a prediction (`IPRED`) of 10 mg/L and we want to show the resulting distribution. For the *classical* approach, we would specify a variance (`EPS(1)`) of 0.0225, and for the *alternative* way, we would specify a CV (`THETA(1)`) of 0.15. What do you think? Will this be equivalent or not? Let’s find out!

```{r}

# Set seed for reproducibility

set.seed(123)

# Parameters

IPRED <- 10

CV_percent <- 0.15

SD_prop <- CV_percent * IPRED

sd_classical <- IPRED * sqrt(0.0225)

# Number of samples

n <- 100000

# Classical way: Specify variance directly

eps_classical <- rnorm(n, mean = 10, sd = sd_classical)

# Alternative way: Specify CV%

eps_alternative <- rnorm(n, mean = 10, sd = 1 * SD_prop)

# Create a tibble combining both distributions

prop_models <- tibble(

value = c(eps_classical, eps_alternative),

source = rep(c("Classical (Variance = 0.0225)", "Alternative (CV = 0.15)"), each = n)

)

# Plot the density of both distributions

prop_models |>

ggplot(aes(x = value, fill = source)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.4) +

labs(

title = "Classical vs. alternative specification",

x = "Concentration [mg/L]",

y = "Density"

) +

scale_fill_manual(

"Model Specification",

values = c(

"Classical (Variance = 0.0225)" = "#003049", # Blue

"Alternative (CV = 0.15)" = "#c1121f" # Red

)

) +

scale_x_continuous(breaks=c(4,6,8,10,12,14,16))+

theme_bw()

```

Both models end up with the same distribution. In the *classical* way, we are given a variance of 0.0225. To get the standard deviation, we take the square root of the variance:

$$

\sigma_{EPS} = \sqrt{0.0225} = 0.15

$$

This means, that our random variable `EPS(1)` has a standard deviation of 0.15 mg/L in our *classical* model:

```{r filename="classical way (proportional)"}

#| eval: false

#| collapse: false

#| code-fold: false

Y = IPRED + IPRED * EPS(1)

```

By multiplying this `EPS(1)` by the prediction (`IPRED`) of 10 mg/L, we are scaling this random variable to have the (desired) standard deviation of the prediction distribution (`PRED`):

$$

\sigma_{Y} = 0.15 \times 10 = 1.5 \, \text{mg/L}

$$

In the *alternative* way, we are directly estimating the coefficient of variation (CV) as 0.15.

```{r filename="alternative way (proportional)"}

#| eval: false

#| collapse: false

#| code-fold: false

SD_PROP = IPRED * THETA(1)

Y = IPRED + SD_PROP * EPS(1)

```

We are first calculating the respective standard deviation (`SD_PROP`) by multiplying `CV` with `IPRED`. We then turn this standard deviation into a random variable with this standard deviation by multiplying it with a random variable from a standard normal (`EPS(1)`). Also here, the respective standard deviation of the prediction distribution (`PRED`) is 1.5 mg/L:

$$

\sigma_{Y} = 0.15 \times 10 = 1.5 \, \text{mg/L}

$$

In both cases, the resulting variability is the same, meaning both approaches lead to the same standard deviation of 1.5 mg/L. Again, it is a bit more convenient to specify the CV directly, as it is more intuitive and easier to interpret. And if the stability argument is true (see above), we would also make our estimation more robust this way.

::: callout-tip

## Specifying proportional RUV in \$THETA gives us a coefficient of variation

Whenever we have a proportional error model and we specify the RUV in the `$THETA` block, the resulting estimate is a coefficient of variation.

:::

## Combined proportional and additive error models

Finally, let's combine our knowledge to understand the *alternative* way of specifying a combined proportional and additive error model:

```{r filename="alternative way (combined)"}

#| eval: false

#| collapse: false

#| code-fold: false

$THETA

0.15 ; RUV_PROP

0.23 ; RUV_ADD

$ERROR

IPRED = F

SD_PROP = THETA(1)*IPRED

SD_ADD = THETA(2)

SD = SQRT(SD_PROP**2 + SD_ADD**2)

Y = IPRED + SD * EPS(1)

$SIGMA

1 FIX

```

Two parts should already be familiar:

```{r filename="alternative way (combined)"}

#| eval: false

#| collapse: false

#| code-fold: false

SD_PROP = THETA(1)*IPRED

SD_ADD = THETA(2)

```

In the first part, we calculate `SD_PROP`, representing the resulting standard deviation of the proportional part (as `THETA(1)` is a CV). The second part, `SD_ADD`, gives us the standard deviation of the additive part. Now we want to find the joint standard deviation `SD` at the given concentration. But how do we combine these components?

```{r filename="alternative way (combined)"}

#| eval: false

#| collapse: false

#| code-fold: false

SD = SQRT(SD_PROP**2 + SD_ADD**2)

```

We can see that we first square both terms, then add them together, then take the square root. Sounds complicated - why not just add them directly together? This is because variances are additive when combining independent random variables, while standard deviations are not [@sochVarianceSumTwo2020]. Written a bit more formally for two independent random variables (we typically assume the covariance to be 0 when modelling RUV):

$$\mathrm{Var}(X + Y) = \mathrm{Var}(X) + \mathrm{Var}(Y)$$

In our case, `SD_PROP` and `SD_ADD` are standard deviations, so we must first square them to get the variances and then add them. However, we want to go back to a standard deviation before we multiply `SD` with `EPS(1)` (being fixed to 1). Therefore, we take the square root in the end.

This operation has always confused me a bit, but once I understood that I can sum up variances, but not standard deviations [^5] it made more sense to me.

::: callout-tip

## Combined error models

When specifying a combined error model, the estimates in the $THETA block represent a standard deviation for the additive part and a coefficient of variation for the proportional part.

:::

## Conclusion

This is a somewhat lengthy explanation of why and how we code the *alternative* approach in NONMEM. Personally, I wasn't very familiar with how distributions behave when its random variable is being multiplying by a factor, and I didn’t realize that while variances are additive when combining two random processes, standard deviations are not. If you have a stronger background in statistics, this might have been obvious, but I hope this explanation was still helpful for some others.

[^1]: Yeah, I know, not really fancy. But that's how it feels when you touch a combined error model for the first time.

[^2]: For many of you, this is likely quite standard. The naming reflects my perspective.

[^3]: I'm not sure if this was initially introduced by one of the Uppsala groups or if this is just some hearsay.

[^4]: Some people also code it with `W` instead of `SD` but it's always a good idea to find descriptive variable names.

[^5]: Probably something you would tackle in the first semester of your statistics studies. But not if you study pharmacy ;)